I am the director of the Ohio State University Acarology Collection, one of the largest university mite collections in the country. Acarology is the science of mites, just like entomology is the science of insects, and ornithology deals with birds. And just to be clear, ticks are mites, big mites, but still mites.

As a little background, my road to Ohio State started with a degree in biology at what is now called the Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. That is also where I got interested in mites. From there I went to the University of Michigan to get my PhD with Barry OConnor, working on systematics of mange mites. My first postdoc was with Jim Oliver at the U.S. National Tick Collection at Georgia Southern University, working on systematics of ticks, after which I joined Bill Black’s lab at Colorado State University. That project still dealt with systematics of ticks, but now using molecular approaches. And in 1996 I was hired at Ohio State in the Department of Entomology.

There have been, and still are, researchers at American universities working on mites, but it is quite rare to have a succession of people working on mites. Georgia Southern University is on its second curator of the U.S. National Tick Collection, but only Ohio State University can boast three successive curators/directors of their mite collection. I followed in the footsteps of George Wharton, who founded the collection at the University of Maryland, and Don Johnston. A major reason for this has been the Acarology Summer Program, a training program in mite identification that achieved global recognition. I organized (and taught in) the program for 22 years, until it moved to the University of Arkansas in 2018.

What do we do in acarology? A core activity was and still is description of species. Estimates of the number of mite species in the world vary from 1-10 million, and so far we described about 66,000. There clearly is some room to expand. Descriptions have changed substantially with the addition of molecular data and new imaging techniques. Molecular work includes standard sequencing of small loci, but we have recently added Next Generation Sequencing with population genetic studies of ticks by Paula Lado. Yes, it is possible to get enough DNA for a modest number of markers from a single mite, although the NGS work could only be done on individuals of something the size of ticks (= really enormous mites).

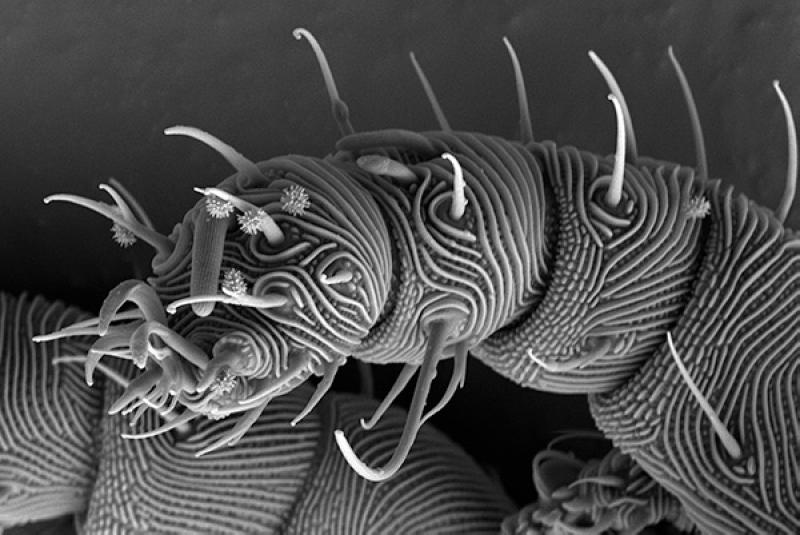

Imaging is one of the more amazing areas of progress. Mites have always had an issue because they are just too small, and specimens on microscope slides, the standard way to study these organisms, are crushed, and do not look particularly attractive. These issues are being resolved by improved techniques in Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and by confocal microscopy. The big advance in SEM was Low Temperature SEM, which allows us to image very soft bodied mites in their natural state. An example of what that looks like is shown in the image of a leg of the “Buckeye dragon mite” as described by my student Sam Bolton. Confocal microscopy allows addition of another dimension, by allowing us to study internal structures. Both Sam Bolton and Orlando Combita have been using this technique to make major advances in understanding mouthpart function (Sam) and evolution of reproductive structures (Orlando). Finally, this technique allows construction of 3D models, so folks can visualize specific structures in their natural state and from multiple angles. I also want to use this technique for outreach, as we can make 3D prints of various mites, helping solve the “too small to see” impediment.

A final area of progress during my time at Ohio State is in databasing. This may not seem as spectacular as imaging of whole genome sequencing, but it may be even more important. With great help from Norman Johnson and his crew, we have databased almost the entire Ohio State Acarology collection (~100,000 slides and vials), and all those data are available on-line (some hiccups right now as we transitioning to a new database system, but the principle remains). As such, this is the largest mite collection in the world to be databased at the specimen level. That means that it is possible to see what mites we have from lizards in Florida or Papua New Guinea. It also means that all that information is no longer locked up in slide boxes or cabinets, it is available for everybody that is interested. This is, of course, an ongoing project: we are currently adding more specimens associated with North American vertebrates and a recently acquired collection of beetle mites.

A brief note on the future. We are currently working on a project funded by the National Science Foundation to revise the Uropodina, a lineage of roughly 40 families and over 2,000 described species. This is likely to be my last major project, as I will be retiring soon. But I plan to go out on a high note, and I feel I am leaving the collection in a better shape than the one that I found in 25 years ago.